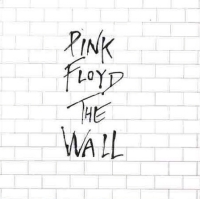

Though the song is relatively simple in terms of narrative (it's mainly used to detail the sexual exploits of rock star Pink whose every sexual fantasy is explored in every town that his tour stops in), the very style that Floyd uses to convey the message contributes to the deeper undertones of the album. It's interesting that Waters described the song as a pastiche, a literary imitation usually for the sake of satire. In one way, the pastiche technique is used to criticize a certain type of music or lifestyle without blatantly attacking it. To use a literary example, many of the chapters of James Joyce's masterpiece Ulysses parody other writers, books, and cultural trends of the time in an attack on what Joyce arguably saw as the degeneration of intellectual thought and literature. Although Joyce never mentions a specific writer or book in these parodic sections, his views are loudly proclaimed and his aim is nearly unmistakable. So too is the aim of Pink Floyd's "Young Lust," a parody of every rocker whose used his celebrity for sex and drugs, whose ego is as large as his image, and whose only care is the pursuit of carnal pleasure.

Though the song is relatively simple in terms of narrative (it's mainly used to detail the sexual exploits of rock star Pink whose every sexual fantasy is explored in every town that his tour stops in), the very style that Floyd uses to convey the message contributes to the deeper undertones of the album. It's interesting that Waters described the song as a pastiche, a literary imitation usually for the sake of satire. In one way, the pastiche technique is used to criticize a certain type of music or lifestyle without blatantly attacking it. To use a literary example, many of the chapters of James Joyce's masterpiece Ulysses parody other writers, books, and cultural trends of the time in an attack on what Joyce arguably saw as the degeneration of intellectual thought and literature. Although Joyce never mentions a specific writer or book in these parodic sections, his views are loudly proclaimed and his aim is nearly unmistakable. So too is the aim of Pink Floyd's "Young Lust," a parody of every rocker whose used his celebrity for sex and drugs, whose ego is as large as his image, and whose only care is the pursuit of carnal pleasure.

Going beyond sheer parody, Floyd interestingly uses this technique to further define Pink's character. The very fact that the song is an imitation of popular rock music of the 70's reinforces Pink's lack of individuality at this time in his life. Up until now, he has been molded by his mother, his school, and life itself into a model civilian void of  nearly all traces of distinctiveness. In the movie Pink is punished by his teacher for writing poetry, restrained sexually by his ever-watchful mother, alienated from much of society because he has no father; all of the above have only contributed to the flimsy mask of personality, each incident painting a feature onto the mask rather than adding depth to his character. Fittingly, the first song of his new independence is one that is so full of rock clichés (the gruff, sexual voice; the catchy, melodic hook; the polished guitar solo) that it's hard to grant just one person credit for writing the song. It not only recalls popular musical trends at the time but the vocals are also reminiscent of an earlier Floyd tune called "the Nile Song", according to a Waters interview. Pink is not just a mere shadow of 70's rock and roll but he's also a shadow of his creators' earlier music. But it's only after he fully erupts that Pink finally comprehends the hollow shell that he is and the void of individual nothingness underneath, a realization that further contributes to the completion of the wall and the destruction of whatever self there once was.

nearly all traces of distinctiveness. In the movie Pink is punished by his teacher for writing poetry, restrained sexually by his ever-watchful mother, alienated from much of society because he has no father; all of the above have only contributed to the flimsy mask of personality, each incident painting a feature onto the mask rather than adding depth to his character. Fittingly, the first song of his new independence is one that is so full of rock clichés (the gruff, sexual voice; the catchy, melodic hook; the polished guitar solo) that it's hard to grant just one person credit for writing the song. It not only recalls popular musical trends at the time but the vocals are also reminiscent of an earlier Floyd tune called "the Nile Song", according to a Waters interview. Pink is not just a mere shadow of 70's rock and roll but he's also a shadow of his creators' earlier music. But it's only after he fully erupts that Pink finally comprehends the hollow shell that he is and the void of individual nothingness underneath, a realization that further contributes to the completion of the wall and the destruction of whatever self there once was.

While the song's position on the album denotes a more natural sense of newfound sexual freedom, one might argue that its position in the movie is much more dubious, casting the song in a retaliatory light. By this argument, Pink turns to the sexually willing groupies in order to get even with his unfaithful wife whose infidelity he has just discovered in "What Shall We Do Now?" Pink stays in his trailer for most of the song, only emerging momentarily when he sees a pretty female fan that catches his eye. Although he is obviously annoyed with her when she tries to get his autograph, he nevertheless takes her back to his hotel room, insinuating that he originally intended to do something with her, that is until he has another one of his "turns" in the next song.

While the song's position on the album denotes a more natural sense of newfound sexual freedom, one might argue that its position in the movie is much more dubious, casting the song in a retaliatory light. By this argument, Pink turns to the sexually willing groupies in order to get even with his unfaithful wife whose infidelity he has just discovered in "What Shall We Do Now?" Pink stays in his trailer for most of the song, only emerging momentarily when he sees a pretty female fan that catches his eye. Although he is obviously annoyed with her when she tries to get his autograph, he nevertheless takes her back to his hotel room, insinuating that he originally intended to do something with her, that is until he has another one of his "turns" in the next song.

One might also argue that the movie sequence is little more than an extension of the album version, "serious[ly] romanticizing" the life of a rock star (Waters, DVD). The majority of the song's scenes do little to advance the plot, mostly showing the excesses of celebrity life in the numerous women, abundant food, and flowing  champagne before concluding the song with the groupie following Pink back into his trailer. Despite the scenes' apparent frivolity, there are a few subtleties that rescue the video from being nothing more than justification for sex jokes and female nudity. It's interesting to note that despite this being Pink's sexual anthem (at least on the album), he is probably the character with the least amount of screen time during the song. His absence from the majority of the footage creates a physical separation between the viewer and the character, one that quite possibly parallels Pink's feelings of abandonment and detachment after having discovered his wife's unfaithfulness. This sense of disconnection is further emphasized by the few times Pink is on screen. When the viewer is offered a glimpse of Pink, it is usually through the window of Pink's trailer, producing yet another wall of separation between the viewer and Pink as well as Pink and the rest of the world. Rather than joining his own backstage party, he sits by the window and indifferently watches the festivities outside of this trailer through a dark pair of sunglasses, yet another wall of separation between the external world and himself. Even when he does emerge from his trailer at the end of the song, he quickly retreats back into it when he finds that the female groupie is just another faceless fan in search of an autograph and a wild story. Interestingly, the fan is more persistent than one might expect, trying to take off his glasses to "find out what's behind [his] cold eyes" and following him into his trailer and eventually back to his hotel room, even after Pink has blatantly expressed his exasperation with her. Coupled with the

champagne before concluding the song with the groupie following Pink back into his trailer. Despite the scenes' apparent frivolity, there are a few subtleties that rescue the video from being nothing more than justification for sex jokes and female nudity. It's interesting to note that despite this being Pink's sexual anthem (at least on the album), he is probably the character with the least amount of screen time during the song. His absence from the majority of the footage creates a physical separation between the viewer and the character, one that quite possibly parallels Pink's feelings of abandonment and detachment after having discovered his wife's unfaithfulness. This sense of disconnection is further emphasized by the few times Pink is on screen. When the viewer is offered a glimpse of Pink, it is usually through the window of Pink's trailer, producing yet another wall of separation between the viewer and Pink as well as Pink and the rest of the world. Rather than joining his own backstage party, he sits by the window and indifferently watches the festivities outside of this trailer through a dark pair of sunglasses, yet another wall of separation between the external world and himself. Even when he does emerge from his trailer at the end of the song, he quickly retreats back into it when he finds that the female groupie is just another faceless fan in search of an autograph and a wild story. Interestingly, the fan is more persistent than one might expect, trying to take off his glasses to "find out what's behind [his] cold eyes" and following him into his trailer and eventually back to his hotel room, even after Pink has blatantly expressed his exasperation with her. Coupled with the groupie's resemblance to his wife (at least in my opinion…which is perhaps why Pink was drawn to her in the first place), the fan acts as yet another extension of the wife's insistent attempts to try to break through Pink's wall and truly connect with him. But just as Pink eventually drove his wife to having an affair, he will also drive the female fan away from him before she even glimpses what's behind his disguise in "One of My Turns."

groupie's resemblance to his wife (at least in my opinion…which is perhaps why Pink was drawn to her in the first place), the fan acts as yet another extension of the wife's insistent attempts to try to break through Pink's wall and truly connect with him. But just as Pink eventually drove his wife to having an affair, he will also drive the female fan away from him before she even glimpses what's behind his disguise in "One of My Turns."