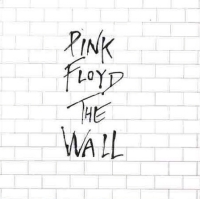

On the DVD commentary, Waters purports that "in some generation you break the cycle for some people." Waters' comments are a perfect foundation for the second part of "When the Tigers Broke Free," a song that serves as both Waters' and Pink's most emotional lament for the loss of a father. Unfortunately for Pink, Waters' comments about the cycle being broken are far from true at this point in the album. Chronologically speaking, young Pink is still erecting his wall brick by brick when he finds a drawer full of war memorabilia containing his father's death certificate sent by "kind old King George." Interestingly, the song's point of view is a departure from that of previous songs, written as a sort of present recollection of past events. Although the events of the song are in the past, it is being told from a present and almost omniscient (i.e. Godlike) point of view, taking into account the third person description of the battle that took Pink's father's life as recounted in the "Tigers, part 1" and a few verses in this second half. Such conflation between the first person personal point of view and the narrator-like third person illustrates just how much of Waters story and personality are tied up with Pink. The creator, while writing a story from the viewpoint of his character, just can't help but slip in his own point of view and experiences. Such an idea is further supported by Waters' real recollections of finding his father's death scroll in a drawer along with a collection of other war memorabilia such as service pistols and ammunition. Accordingly, the emotion of this song is perhaps the most pure of any song on the album in that it stems directly from the creator's own psyche. Whereas other songs mix true events with fiction or combine the lives of a few people into one story, "When the Tigers Broke Free" is an unadultered account of Water's childhood and his father's death, making it, at least for me, the most haunting song on the record…even if it wasn't on the original album!

On the DVD commentary, Waters purports that "in some generation you break the cycle for some people." Waters' comments are a perfect foundation for the second part of "When the Tigers Broke Free," a song that serves as both Waters' and Pink's most emotional lament for the loss of a father. Unfortunately for Pink, Waters' comments about the cycle being broken are far from true at this point in the album. Chronologically speaking, young Pink is still erecting his wall brick by brick when he finds a drawer full of war memorabilia containing his father's death certificate sent by "kind old King George." Interestingly, the song's point of view is a departure from that of previous songs, written as a sort of present recollection of past events. Although the events of the song are in the past, it is being told from a present and almost omniscient (i.e. Godlike) point of view, taking into account the third person description of the battle that took Pink's father's life as recounted in the "Tigers, part 1" and a few verses in this second half. Such conflation between the first person personal point of view and the narrator-like third person illustrates just how much of Waters story and personality are tied up with Pink. The creator, while writing a story from the viewpoint of his character, just can't help but slip in his own point of view and experiences. Such an idea is further supported by Waters' real recollections of finding his father's death scroll in a drawer along with a collection of other war memorabilia such as service pistols and ammunition. Accordingly, the emotion of this song is perhaps the most pure of any song on the album in that it stems directly from the creator's own psyche. Whereas other songs mix true events with fiction or combine the lives of a few people into one story, "When the Tigers Broke Free" is an unadultered account of Water's childhood and his father's death, making it, at least for me, the most haunting song on the record…even if it wasn't on the original album!

As with the first "Tigers," there is little need for a symbolic discussion of the song's lyrics being that they are fairly straightforward. Young Pink finds a scroll sent by the British government announcing his father's death, sparking the conclusion of the war story begun in the "Tigers, part 1." The most interesting aspects about this second part, as with the first, are the subtle connotations in the lyrics that give a bit of emotional insight into the narrator's mind. With the first part, words like "miserable" and "ordinary" belie the narrator's seemingly detached point of view, hinting at the cynicism and grief behind the composed voice. The second part is no different though perhaps much more effective in that the narrator is finally given an identity and the grief hinted at in the first part is fully and painfully evident towards the end of the song. The narrator's pain builds as he recalls finding physical proof of his father's death and is conceivably compounded by the fact that his father's death was nothing more than routine for the English government. The honor inherent in the scroll form and gold leaf is tainted by the king's signature in the form of a rubber stamp, implying that the father's life and the lives destroyed by the war are merely inconsequential and replaceable components of the factory-like workings of the English government. Not only did the King not sign the death certificate of one who gave his life for the crown but also some lesser government employee, another cog in the great metaphorical machine of politics, most likely stamped the king's insignia on the scroll. As a result, there is little wonder why Pink vehemently attacks the High Command for taking "my daddy from me," a feeling of personal betrayal by the social systems that resurfaces later in the album in songs like "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" and "Mother." The accusations of governmental betrayal continue when Pink recounts that "they [the soldiers] were all left behind," either dead or dying after the Tigers (the German war tanks) attacked the Anzio bridgehead. Although it's most likely improbable that the British government candidly betrayed its own forces, it is certainly reasonable for Pink to feel such

With the first part, words like "miserable" and "ordinary" belie the narrator's seemingly detached point of view, hinting at the cynicism and grief behind the composed voice. The second part is no different though perhaps much more effective in that the narrator is finally given an identity and the grief hinted at in the first part is fully and painfully evident towards the end of the song. The narrator's pain builds as he recalls finding physical proof of his father's death and is conceivably compounded by the fact that his father's death was nothing more than routine for the English government. The honor inherent in the scroll form and gold leaf is tainted by the king's signature in the form of a rubber stamp, implying that the father's life and the lives destroyed by the war are merely inconsequential and replaceable components of the factory-like workings of the English government. Not only did the King not sign the death certificate of one who gave his life for the crown but also some lesser government employee, another cog in the great metaphorical machine of politics, most likely stamped the king's insignia on the scroll. As a result, there is little wonder why Pink vehemently attacks the High Command for taking "my daddy from me," a feeling of personal betrayal by the social systems that resurfaces later in the album in songs like "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2" and "Mother." The accusations of governmental betrayal continue when Pink recounts that "they [the soldiers] were all left behind," either dead or dying after the Tigers (the German war tanks) attacked the Anzio bridgehead. Although it's most likely improbable that the British government candidly betrayed its own forces, it is certainly reasonable for Pink to feel such  overwhelming bitterness towards the government for sending his father to death and subsequently treating that death as simply another statistic.

overwhelming bitterness towards the government for sending his father to death and subsequently treating that death as simply another statistic.

Another interesting lyrical aspect in the song is the apparent allusions, whether intentional or not, to the imagery in previous songs and the larger themes of the album. Pink finds the scroll in "a drawer of old photographs, hidden away," a lyric reminiscent of the memory of Pink's father as "a snapshot in the family album" from "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1." Ideas of the subconscious and repression are immediately recalled with the "old photographs" symbolically representing the memories hidden and forgotten in the "drawer" of one's mind. In other words, Pink's discovery of the scroll symbolizes the repressed emotions and memories that must eventually resurface, spawning the emotional outburst in the latter part of "Tigers, Part 2." As mentioned before, this cycle of repression, remembering, and emotional outburst is found throughout the album with "Tigers" acting as an example of just how early these cycles start. Another possible allusion is the "frost in the ground" during the Anzio battle, recalling the images of frozenness and sterility from "the Thin Ice." As with this previous song, the frost in "Tigers" reminds the viewer of the futility and fragility of Life, the burdens placed on us all (in this case, the burden of war), and every man's eventual demise.

There is little narrative development during the movie scenes for this song although the emotional impact is immense. True to the song's narrative, Young Pink (now around the age of 12 - 13) comes home from school and finds his father's death certificate in the bottom drawer of a dresser in his mother's room. Along with the scroll he finds a shaving razor, a very male symbol, Waters muses on the DVD, and one that is missing from his life, as well as a box of bullets. Beneath it all he finds his father's military uniform, which he puts on in front of the mirrors of his mother's bureau. The following shots are equally haunting and powerful, cutting between shots of Young Pink and his father in the same outfit. These shots further illustrate Waters' ideas of cycles with the young taking the place (and the burdens) of the old. Pink's father wears the uniform of his country and takes on the burden of the war being waged. Pink wears the uniform of his father and takes on both the burden of losing that very same father as well as the effects the war has had on the country and the world. In a strict metaphorical sense, the father is Pink's doppelganger (and vice versa), acting as the ghostly double of Pink. In other words, Pink and his father are mirror images of each other, fighting a war neither asked for (whether real or metaphorical) and carrying the burdens of the previous generation. This idea of the doubled self is further compounded by the fact that the viewer sees the subjects (Pink / Father) through the mirrors of the bedroom bureau rather than by actually looking at  the subjects themselves. It's also interesting to note that the shots of Pink's father are mainly stationary while the shots of Pink in the uniform pan his image in the side and main mirrors of the bureau, hinting at Pink's more fractured identity. Perhaps this is a result of the looking at himself through his mother's mirror. Symbolically, mirrors represent anything from the true self, the way one views oneself, or the way one wants others to view one. The mirror images of Pink reveal all of the above, revealing Pink as he is (the young boy beneath the uniform), Pink as the metaphorical extension of his father (Pink in uniform), and the way Pink's mother views Pink as both child and vessel for her feelings over the loss of her husband (Pink in uniform as reflected in mother's mirror). Each separate mirror image is another fracture in Pink's persona, another brick in his ever-growing wall accounting for the split of his identity later in the album and movie.

the subjects themselves. It's also interesting to note that the shots of Pink's father are mainly stationary while the shots of Pink in the uniform pan his image in the side and main mirrors of the bureau, hinting at Pink's more fractured identity. Perhaps this is a result of the looking at himself through his mother's mirror. Symbolically, mirrors represent anything from the true self, the way one views oneself, or the way one wants others to view one. The mirror images of Pink reveal all of the above, revealing Pink as he is (the young boy beneath the uniform), Pink as the metaphorical extension of his father (Pink in uniform), and the way Pink's mother views Pink as both child and vessel for her feelings over the loss of her husband (Pink in uniform as reflected in mother's mirror). Each separate mirror image is another fracture in Pink's persona, another brick in his ever-growing wall accounting for the split of his identity later in the album and movie.